The Comic as Object Project

This project starts with a basic, and I think self-evident, premise taken from a different medium altogether – that a video call is not the same as an in-person meeting.

Sure, there are advantages and benefits to virtual meetings, but trade-offs as well.

And if the pandemic has reminded us of nothing else, being in a room together – being in physical contact – is the richest and most basic form of human interaction.

So too for comics and graphic novels, available these days in a diversity of formats both analog and digital, but with roots in the ‘real’ world as physical objects.

While there are advantages and benefits to e-comics and web comics, especially around cost of production, distribution, and accessibility, it should not be surprising that many successful web comics later (re)appear in physical book form.

But we’re curious to further explore why…

As part of our Head Alien’s ongoing studies at the University of Alberta School of Library and Information Studies, this project is also serving as the basis for a virtual seminar for LIS 518: Comic Books and Graphic Novels in School and Public Libraries.

Our ultimate goal, for my classmates and our readers here, is to introduce another layer or lens through which to experience and enjoy comics and graphic novels.

Submitted June 25, 2023.

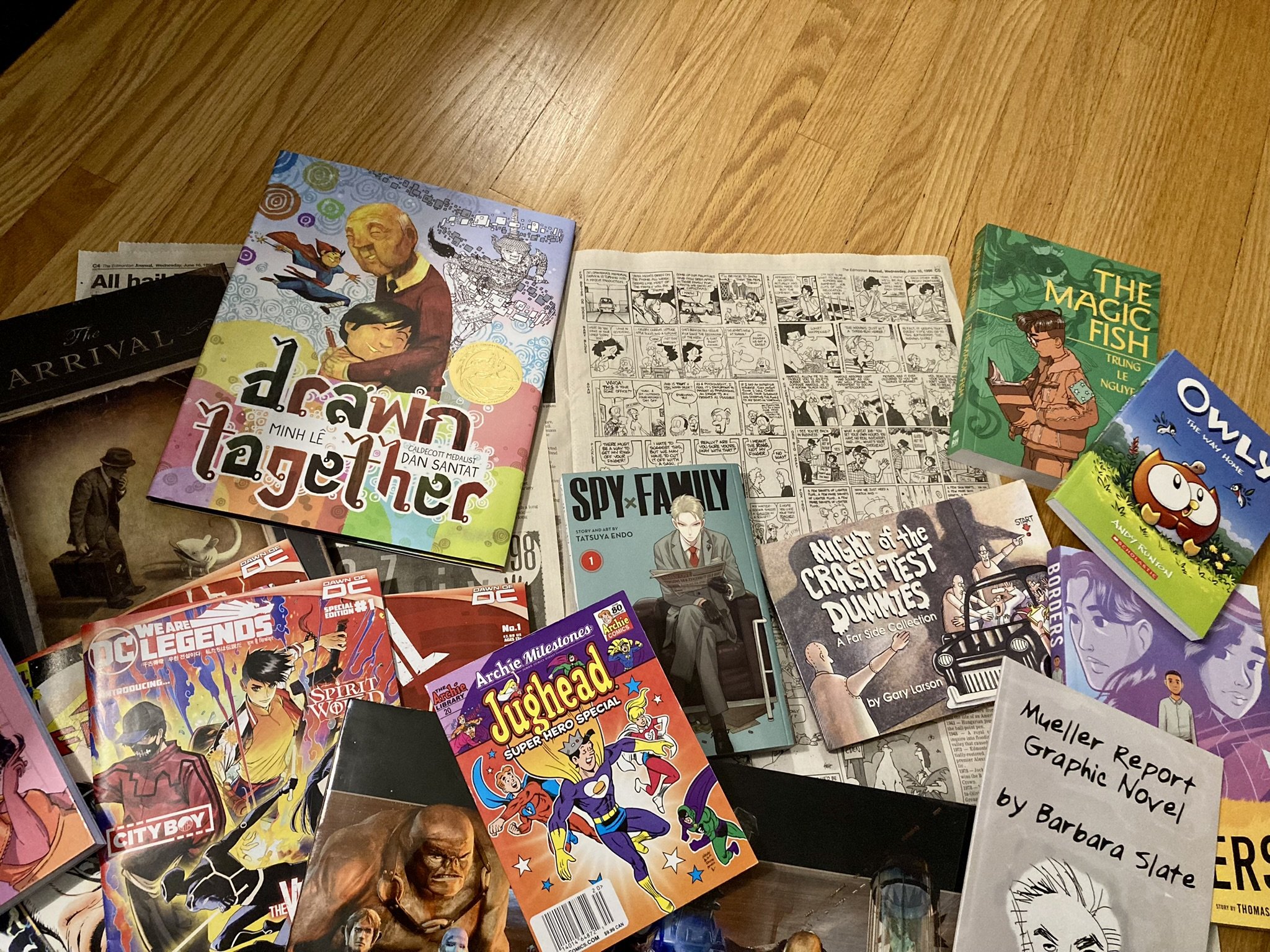

Banner image above: Photo of a selection of our Head Alien’s comics, comic books, and graphic novels piled on his living room floor.

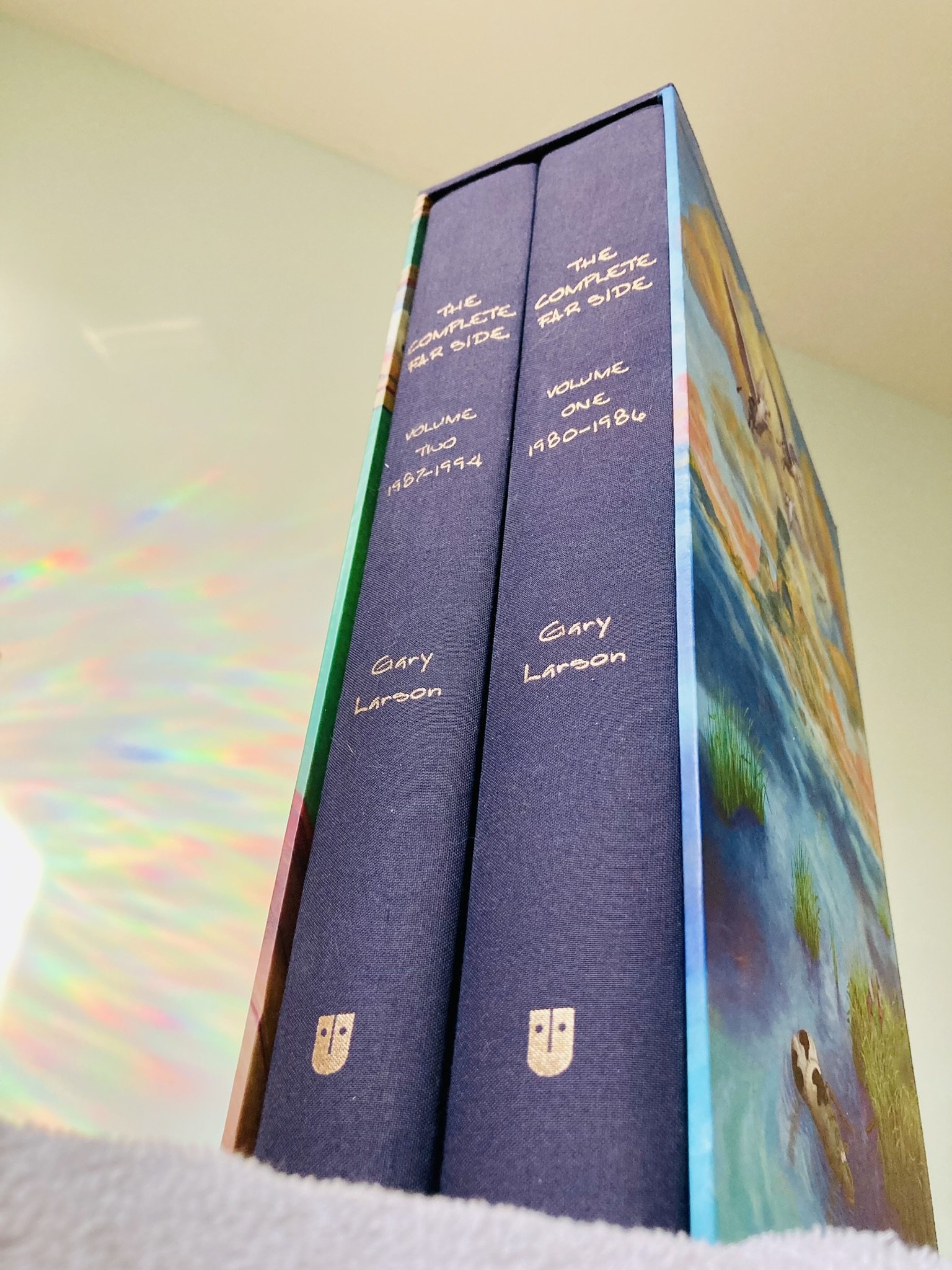

Feature image above: Our Head Alien’s slipcased hardcover edition of The Complete Far Side, Volumes 1 & 2, by Gary Larson.

A philosophical starting point or two…

Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation

As a foundation for exploring our case studies, I first want to introduce the idea of paratexts as first described by French scholar Gerard Genette in his book Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (1997).

Genette describes paratexts as “what enables a text to become a book and to be offered as such to its readers and, more generally, to the public. More than a boundary or a sealed border, the paratext is, rather, a threshold” (p.1-2).

Originally conceptualized in relation to ‘literary’ works, Genette’s concept presumes that a literary work consists of “a text, defined (very minimally) as a more or less long sequence of verbal statements that are more or less endowed with significance. But this text is rarely presented in a unadorned state, unreinforced and unaccompanied by a certain number of verbal and other productions… precisely in order to present it, in the usual sense of this verb but also in the strongest sense: to make present, to ensure the text’s presence in the world” (p.1).

Paratextual elements can be further subdivided into peritexts which directly connect to the main text – for example, the title, author’s name, book format, and prefaces and notes – and epitexts which halo the main text – things like publisher’s promotional materials, reviews, and even private correspondance about the book.

What’s interesting in the context of graphic novels and comics is that sometimes a central text by Genette’s definition – “a more or less long sequence of verbal statements” – does not even exist, for example in a wordless graphic novel like Shaun Tan’s The Arrival. Rather, the “text” or core story is conveyed entirely non-verbally through elements that may, or may not, also be considered paratextual. Or that might be considered paratextual in a primarily written work, but make up the core “text” in the world of graphica.

Furthermore, comics and graphic novels introduce many additional elements of paratext not specifically addressed by Genette in his book. But conceptually Genette’s overall approach does still apply well.

As a result, this idea of identifying and naming the ‘threshold’ and its elements – the things that actually “make present” a book – provides a critical foundation for looking at comics as objects.

The Field of Cultural Production

The other concept I want to bring into this discussion is the idea of cultural capital or symbolic capital as explored by another French thinker, Pierre Bourdieu (2006).

In his article titled “The Field of Cultural Production," Bourdieu explores many of the same concepts we have touched on in LIS 518 around literary and cultural hierarchies – comics being ‘second-class literature’ or ‘just for kids’ – but exploring in even more depth their relationship to economic production and also systems of power.

Of particular note to me is the dichotomy around producing ‘art for art’s sake’ in contrast to ‘appealing to the mass market’ (an oversimplified if not outright false dichotomy) as being somehow correlated to a focus on long-term versus short-term economic gain, and all the social judgments that accompany that kind of thinking. This is the type of underlying dynamic that Bourdieu would argue has contributed to, for example, the dismissal of mass market romances sold at the grocery store as a lesser form of writing than poetry or ‘literary’ fiction sold at ‘an independent bookseller.’

And even as we look at the phenomenon of comics and graphic novels overall being dismissed as lesser or just a stepping stone to ‘real’ literature, we can also see ideas of cultural and symbolic capital being played out at a more micro level as well, in the distinction between comics versus graphic novels, graphic novel adaptations versus ‘media-native’ graphic novels, and any other number of distinctions, valid or otherwise.

Image in back: UPC barcode for The Vigil, No. 2.

Front image: ISBN barcode for Spy Family, Vol. 1.

Sidebar: UPC vs ISBN

Bringing together the idea of paratexts and symbolic capital – the literal and figurative of a book’s existence, if you will – I wanted to take us on a small knowledge side quest into one particular element that will come up again in our case studies.

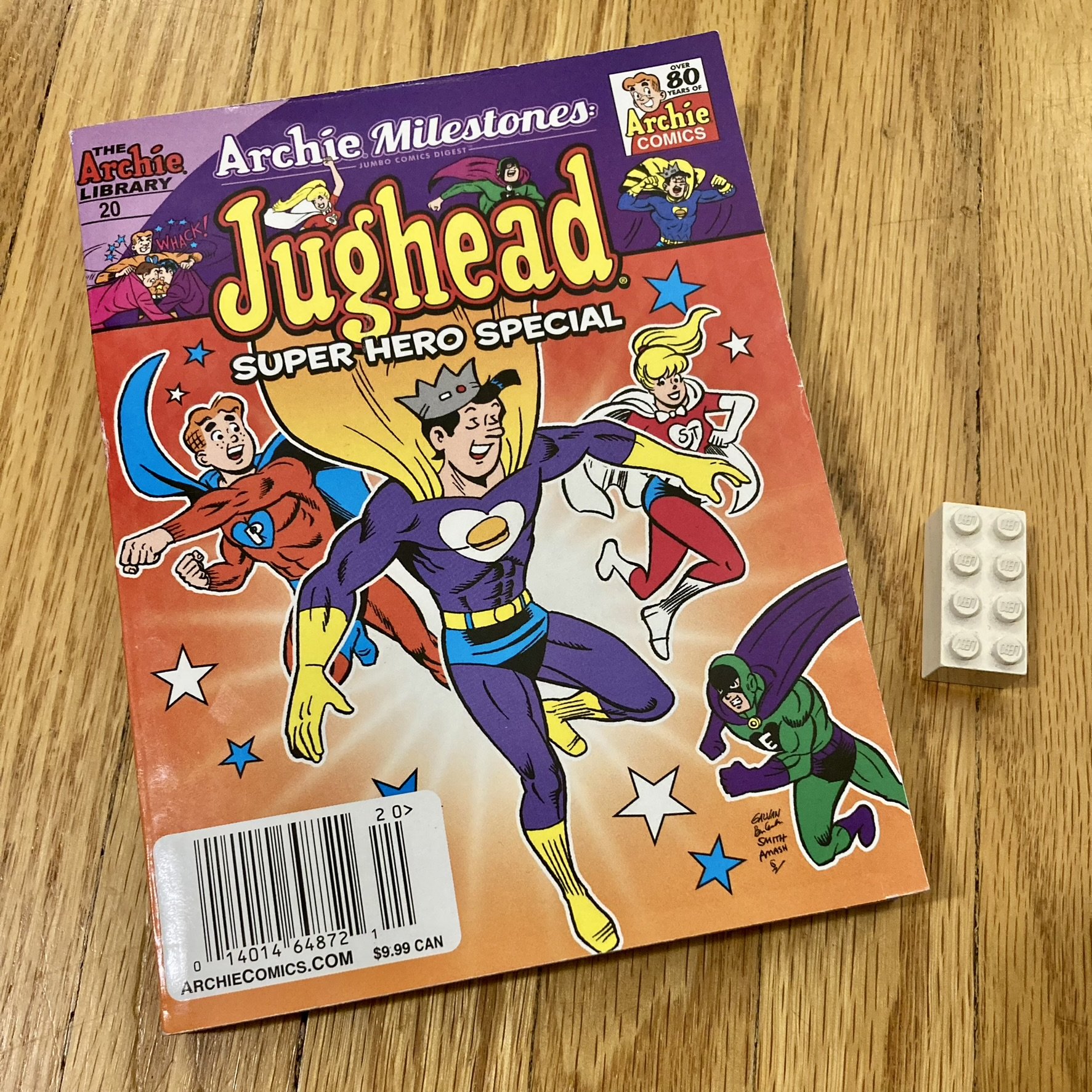

Because comics are considered ‘serials’ – which one could read as ‘more disposable,’ like a magazine or newspaper – individual issues are assigned UPCs – universal product codes – as opposed to ISBNs – international standard book numbers – the way books, including graphic novels, are.

While both UPCs and ISBNs are fundamentally and similarly commercial in function, there is a level of social hierarchy to having a ‘product code’ versus a ‘book number.’ Taken a step even further, some ‘fine press’ publishers, like The Folio Society or the Easton Press, consider themselves above even having ISBNs assigned to their titles much less besmirching their actual books with a barcode. Meanwhile, while such publishers may choose not to have an ISBN, Library and Archives Canada specifically declares comics as ineligible to get one.

One direct effect is that we are unable to scan comics into our online catalogues here at the Butterflies & Aliens Library using their barcodes, the way we can quickly with books published since 2005, and instead have to add them in manually. Nor can you search up comics by their UPC in any major book-related database, including at Audreys Books, the Edmonton Public Library, Chapters Indigo, or even Amazon. (you can sometimes look up entire series using their ISSN – International Standard Serial Number – but that’s a whole other post!)

Keep this ‘microaggression’ in mind as we explore further.

A final metaphor before diving in…

… and it’s not necessarily a great one, but it’s a place to start: if the writing is what the book is saying and the artwork is how the book is moving, with voice and tone and timbre carried somewhere between the two, I would argue that the object in which these things are literally embodied, whether conveyed directly or virtually, is the body of the book and where a third layer of meaning is conveyed – the book version of its body language.

So as we explore some case studies of comics and graphic novels, and how their particular bodies inform our reading, we hope you’ll discover some new ways to encounter and interact with this already diverse and diverting format/genre/class of books.

Happy reading!

– Winston

Case Studies

Post Script

The Comic as Object Project was originally posted June 25, 2023.

Other Resources

If you’ve found this project topic interesting, you’re invited to also check out our Book Cover Project as well as browsing our stacks for posts about the Book as Object, Altered Books, and Design.

Happy exploring!

Works Cited and Consulted

Bar Code Graphics (2021). Guidance for UPC barcodes for Comic Books. https://www.barcode.graphics/guidance-for-upc-barcodes-for-comic-books/

Bourdieu, P. (2006). The Field of Cultural Production. In D. Finkelstein, & A. McCleery (Eds.), The Book History Reader, Second Edition (pp. 99-120). Routledge.

Finkelstein, D. & McCleery, A. (Eds.). (2006). The Book History Reader, Second Edition. Routledge.

Genette, G. (1997). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (J. E. Lewin, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1987).

Library and Archives Canada (2022, Sept 9). About ISBNs. https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/services/publishers/isbn/Pages/about-isbns.aspx

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. William Morrow.

Tan, S. (2007). The Arrival. Arthur A. Levine Books.

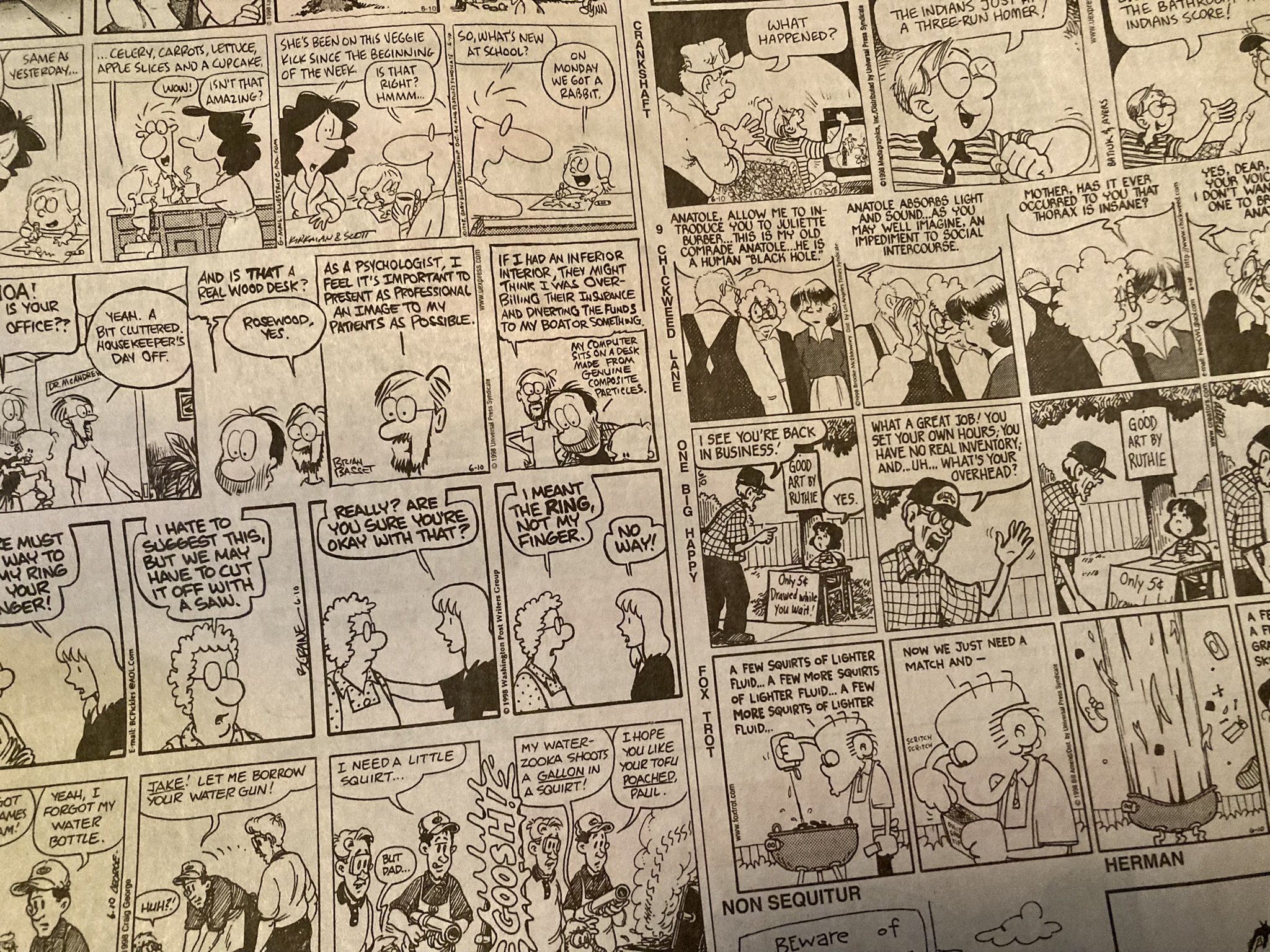

Once upon a time I had a shoebox full of favourite comic strips that I had diligently cut out of the newspaper… Calvin & Hobbes, The Far Side, Bloom County, to name but a few. Somewhere over time and over moves, I lost that box, much to my sadness.

But if the strip got popular enough, some publisher would come along and reprint them into a little book…